5.1 From Tables to Lists

Previously [Introduction to Tabular Data] we began to process collective data in the form of tables. Though we saw several powerful operations that let us quickly and easily ask sophisticated questions about our data, they all had two things in common. First, all were operations by rows. None of the operations asked questions about an entire column at a time. Second, all the operations not only consumed but also produced tables. However, we already know [Getting Started] there are many other kinds of data, and sometimes we will want to compute one of them. We will now see how to achieve both of these things, introducing an important new type of data in the process.

5.1.1 Basic Statistical Questions

The most-frequently used discount code.

The average number of tickets per order.

The largest ticket order.

The most common number of tickets in an order.

The collection of unique discount codes that were used (many might have been available).

The collection of distinct email addresses associated with orders, so we can contact customers (some customers may have placed multiple orders).

Which school lead to the largest number of orders with a

"STUDENT"discount.

Do Now!

Think about whether and how you would express these questions with the operations you have already seen.

In each of these cases, we need to perform a computation on a single

column of data (even in the last question about the "STUDENT"

discount, as we would filter the table to those rows, then do a

computation over the email column). In order to capture these

in code, we need to extract a column from the table.

For the rest of this chapter, we will work with a cleaned copy of the

event-data from the previous chapter. The cleaned data, which

applies the transformations at the end of the previous chapter, is in

a different tab of the same Google Sheet as the other versions of the

event data.

ssid = "1DKngiBfI2cGTVEazFEyXf7H4mhl8IU5yv2TfZWv6Rc8"

cleaned-data =

load-table: name, email, tickcount, discount, delivery

source: load-spreadsheet(ssid).sheet-by-name("Cleaned", true)

sanitize name using string-sanitizer

sanitize email using string-sanitizer

sanitize tickcount using num-sanitizer

sanitize discount using string-sanitizer

sanitize delivery using string-sanitizer

end5.1.2 Extracting a Column from a Table

Our collection of table functions includes one that we haven’t yet

used, called select-columns. As the name suggests, this

function produces a new table containing only certain columns from an

existing table. Let’s extract the tickcount column so we can

compute some statistics over it. We use the following expression:

select-columns(cleaned-data, [list: "tickcount"])

This focuses our attention on the numeric ticket sales, but we’re still stuck with a column in a table, and none of the other tables functions let us do the kinds of computations we might want over these numbers. Ideally, we want the collection of numbers on their own, without being wrapped up in the extra layer of table cells.

In principle, we could have a collection of operations on a single column. In some languages that focus solely on tables, such as SQL, this is what you’ll find. However, in Pyret we have many more kinds of data than just columns (as we’ll soon see [Introduction to Structured Data], we can even create our own!), so it makes sense to leave the gentle cocoon of tables sooner or later. An extracted column is a more basic kind of datum called a list, which can be used to represent a sequence of data outside of a table.

Just as we have used the notation .row-n to pull a single row

from a table, we use a similar dot-based notion to pull out a single

column. Here’s how we extract the tickcount column:

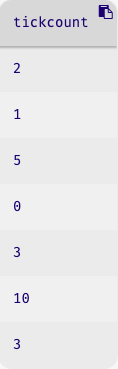

cleaned-data.get-column("tickcount")In response, Pyret produces the following value:

[list: 2, 1, 5, 0, 3, 10, 3]Now, we seem to have only the values that were in the cells in the

column, without the enclosing table. Yet the numbers are still bundled

up, this time in the [list: ...] notation. What is that?

5.1.3 Understanding Lists

The elements have an order, so it makes sense to talk about the “first”, “second”, “last”—

and so on— element of a list. All elements of a list are expected to have the same type.

5.1.3.1 Lists as Anonymous Data

This might sound rather abstract—3 or -1: what is it? It’s the same sort of thing: an

anonymous value that does not describe what it represents; the

interpretation is done by our program. In one setting 3 may

represent an age, in another a play count; in one setting -1

may be a temperature, in another the average of several

temperatures. Similarly with a string: Is "project" a noun (an

activity that one or more people perform) or a verb (as when we

display something on a screen)? Likewise with images and so on. In

fact, tables have been the exception so far in having description

built into the data rather than being provided by a program!

This genericity is both a virtue and a problem. Because, like other anonymous data, a list does not provide any interpretation of its use, if we are not careful we can accidentally mis-interpret the values. On the other hand, it means we can use the same datum in several different contexts, and one operation can be used in many settings.

Indeed, if we look at the list of questions we asked earlier, we see

that there are several common operations—

5.1.3.2 Creating Literal Lists

get-column. As you might expect, however, we can also create lists

directly:

[list: 1, 2, 3]

[list: -1, 5, 2.3, 10]

[list: "a", "b", "c"]

[list: "This", "is", "a", "list", "of", "words"]shopping-list = [list: "muesli", "fiddleheads"]Do Now!

Based on these examples, can you figure out how to create an empty list?

As you might have guessed, it’s [list: ] (the space isn’t

necessary, but it’s a useful visual reminder of the void).

5.1.4 Operating on Lists

5.1.4.1 Built-In Operations on Lists of Numbers

Pyret handily provides a useful set of operations we can already perform on lists. The lists documentation describes these operations. As you might have guessed, we can already compute most of the answers we’ve asked for at the start of the chapter. First we need to include some libraries that contain useful functions:

import math as M

import statistics as Stickcounts = cleaned-data.get-column("tickcount")

M.max(tickcounts) # largest number in a list

M.sum(tickcounts) # sum of numbers in a list

S.mean(tickcounts) # mean (average) of numbers in a list

S.median(tickcounts) # median of numbers in a listThe M. notation means "the function inside the library

M. The import statement in the above code gave the name

M to the math library.

5.1.4.2 Built-In Operations on Lists in General

Some of the useful computations in our list at the start of the

chapter involved the discount column, which contains strings

rather than numbers. Specifically, let’s consider the following

question:

Compute the collection of unique discount codes that were used (many might have been available).

None of the table functions handle a question like this. However, this is a common kind of question to ask about a collection of values (How many unique artists are in your playlist? How many unique faculty are teaching courses?). As such, Pyret (as most languages) provides a way to identify the unique elements of a list. Here’s how we get the list of all discount codes that were used in our table:

import lists as L

codes = cleaned-data.get-column("discount")

L.distinct(codes)The distinct function produces a list of the unique values from

the input list: every value in the input list appears exactly once in

the output list. For the above code, Pyret produces:

[list: "BIRTHDAY", "STUDENT", "none"]What if we wanted to exclude "none" from that list? After all,

"none" isn’t an actual discount code, but rather one that we

introduced while cleaning up the table. Is there a way to easily

remove "none" from the list?

There are two ways we could do it. In the Pyret lists documentation,

we find a function called remove, which removes a specific

element from a list:

| |

|

But this operation should also sound familiar: with tables, we

used filter-with to keep only those elements that meet a

specific criterion. The filtering idea is so common that Pyret (and

most other languages) provide a similar operation on lists. In the

case of the discount codes, we could also have written:

fun real-code(c :: String) -> Boolean:

not(c == "none")

end

L.filter(real-code, L.distinct(codes))The difference between these two approaches is that filter is

more flexible: we can check any characteristic of a list element using

filter, but remove only checks whether the entire

element is equal to the value that we provide. If instead of removing

the specific string "none", we had wanted to remove all strings

that were in all-lowercase, we would have needed to use filter.

Exercise

Write a function that takes a list of words and removes those words in which all letters are in lowercase. (Hint: combine

string-to-lowerand==).

5.1.4.3 An Aside on Naming Conventions

Our use of the plural codes for the list of values in the

column named discount (singular) is deliberate. A list contains

multiple values, so a plural is appropriate. In a table, in contrast,

we think of a column header as naming a single value that appears in

a specific row. Often, we speak of looking up a value in a specific

row and column: the singular name for the column supports thinking

about lookup in an individual row.

5.1.4.4 Getting Elements By Position

Let’s look at a new analysis question: the events company recently ran

an advertising campaign on web.com, and they are curious

whether it paid off. To do this, they need to determine how many sales

were made by people with web.com email addresses.

Do Now!

Propose a task plan (Task Plans) for this computation.

Here’s a proposed plan, annotated with how we might implement each part:

Get the list of email addresses (use

get-column)Extract those that came from

web.com(useL.filter)Count how many email addresses remain (using

L.length, which we hadn’t discussed yet, but it is in the documentation)

(As a reminder, unless you immediately see how to solve a problem, write out a task plan and annotate the parts you know how to do. It helps break down a programming problem into more manageable parts.)

Let’s discuss the second task: identifying messages from

web.com. We know that email addresses are strings, so if we

could determine whether an email string ends in @web.com,

we’d be set. You could consider doing this by looking at the last 7

characters of the email string. Another option is to use a string

operation that we haven’t yet seen called string-split-all, which

splits a string into a list of substrings around a given

character. For example:

| |

|

| |

|

This seems pretty useful. If we split each email string around the

@ sign, then we can check whether the second string in the

list is web.com (since email addresses should have only one

@ sign). But how would we get the second element out of

the list produced by string-split-all? Here we dig into the

list, as we did to extract rows from tables, this time using the

get operation.

| |

|

Do Now!

Why do we use

1as the input togetif we want the second item in the list?

Here’s the complete program for doing this check:

fun web-com-address(email :: String) -> Boolean:

doc: "determine whether email is from web.com"

string-split(email, "@").get(1) == "web.com"

where:

web-com-address("bonnie@pyret.org") is false

web-com-address("parrot@web.com") is true

end

emails = cleaned-data.get-column("email")

L.length(L.filter(web-com-address, emails))Exercise

What happens if there is a malformed email address string that doesn’t contain the

@string? What would happen? What could you do about that?

5.1.4.5 Transforming Lists

Imagine now that we had a list of email addresses, but instead just wanted a list of usernames. This doesn’t make sense for our event data, but it does make sense in other contexts (such as connecting messages to folders organized by students’ usernames).

Specifcally, we want to start with a list of addresses such as:

[list: "parrot@web.com", "bonnie@pyret.org"]and convert it to

[list: "parrot", "bonnie"]Do Now!

Consider the list functions we have seen so far (

distinct,filter,length) – are any of them useful for this task? Can you articulate why?

One way to articulate a precise answer to this is think in terms of

the inputs and outputs of the existing functions. Both filter

and distinct return a list of elements from the input list, not

transformed elements. length returns a number, not a list. So

none of these are appropriate.

This idea of transforming elements is similar to the

transform-column operation that we previously saw on

tables. The corresponding operation on lists is called

map. Here’s an example:

fun extract-username(email :: String) -> String:

doc: "extract the portion of an email address before the @ sign"

string-split(email, "@").get(0)

where:

extract-username("bonnie@pyret.org") is "bonnie"

extract-username("parrot@web.com") is "parrot"

end

L.map(extract-username,

[list: "parrot@web.com", "bonnie@pyret.org"])5.1.4.6 Recap: Summary of List Operations

At this point, we have seen several useful built-in functions for working with lists:

filter :: (A -> Boolean), List<A> -> List<A>, which produces a list of elements from the input list on which the given function returnstrue.map :: (A -> B), List<A> -> List<B>, which produces a list of the results of calling the given function on each element of the input list.distinct :: List<A> -> List<A>, which produces a list of the unique elements that appear in the input list.length :: List<A> -> Number, which produces the number of elements in the input list.

Here, a type such as List<A> says that we have a list whose

elements are of some (unspecified) type which we’ll call

A. A type variable such as this is useful when we want to

show relationships between two types in a function

contract. Here, the type variable A captures that the type of

elements is the same in the input and output to filter. In

map, however, the type of element in the output list could

differ from that in the input list.

One additional built-in function that is quite useful in practice is:

member :: List<A>, Any -> Boolean, which determines whether the given element is in the list. We use the typeAnywhen there are no constraints on the type of value provided to a function.

Many useful computations can be performed by combining these operations.

Exercise

Assume you used a list of strings to represent the ingredients in a recipe. Here are three examples:

stir-fry = [list: "peppers", "pork", "onions", "rice"] dosa = [list: "rice", "lentils", "potato"] misir-wot = [list: "lentils", "berbere", "tomato"]Write the following functions on ingredient lists:

recipes-uses, which takes an ingredient list and an ingredient and determines whether the recipe uses the ingredient.

make-vegetarian, which takes an ingredient list and replaces all meat ingredients with"tofu". Meat ingredients are"pork","chicken", and"beef".

protein-veg-count, which takes an ingredient list and determines how many ingredients are in the list that aren’t"rice"or"noodles".

Exercise

More challenging: Write a function that takes two ingredient lists and returns all of the ingredients that are common to both lists.

Exercise

Another more challenging: Write a function that takes an ingredient and a list of ingredient lists and produces a list of all the lists that contain the given ingredient.

Hint: write examples first to make sense of the problem as needed.

5.1.5 Lambda: Anonymous Functions

Let’s revisit the program we wrote earlier in this chapter for finding all of the discount codes that were used in the events table:

fun real-code(c :: String) -> Boolean:

not(c == "none")

end

L.filter(real-code, codes)This program might feel a bit verbose: do we really need to write a

helper function just to perform something as simple as a

filter? Wouldn’t it be easier to just write something like:

L.filter(not(c == "none"), codes)Do Now!

What will Pyret produce if you run this expression?

Pyret will produce an unbound identifier error around the use

of c in this expression. What is c? We mean for c

to be the elements from codes in turn. Conceptually, that’s

what filter does, but we don’t have the mechanics right. When

we call a function, we evaluate the arguments before the body

of the function. Hence, the error regarding c being unbound.

The whole point of the real-code helper function is to make

c a parameter to a function whose body is only evaluated once

values for c is available.

To tighten the notation as in the one-line filter expression,

then, we have to find a way to tell Pyret to make a temporary function

that will get its inputs once filter is running. The following

notation achieves this:

L.filter(lam(c): not(c == "none") end, codes)We have added lam(c) and end around the expression that

we want to use in the filter. The lam(c) says "make a

temporary function that takes c as an input". The end

serves to end the function definition, as when we use

fun. lam is short for lambda, a form of function

definition that exists in many, though not all, languages.

The main difference between our original expression (using the

real-code helper) and this new one (using lam) can be

seen through the program directory. To explain this, a little detail

about how filter is defined under the hood. In part, it looks

like:

fun filter(keep :: (A -> Boolean), lst :: List<A>) -> List<A>:

if keep(<elt-from-list>):

...

else:

...

end

endWhether we pass real-code or the lam version to

filter, the keep parameter ends up referring to a

function with the same parameter and body. Since the function is only

actually called through the keep name, it doesn’t matter

whether or not a name is associated with it when it is initially

defined.

In practice, we use lam when we have to pass simple (single

line) functions to operations like filter (or map). We

could have just as easily used them when we were working with tables

(build-column, filter-with, etc). Of course, you can

continue to write out names for helper functions as we did with

real-code if that makes more sense to you.

Exercise

Write the program to extract the list of usernames from a list of email addresses using

lamrather than a named helper-function.

5.1.6 Combining Lists and Tables

The table functions we studied previously were primarily for processing rows. The list functions we’ve learned in this chapter have been primarily for processing columns (but there are many more uses in the chapters ahead). If an analysis involves working with only some rows and some columns, we’ll use a combination of both table and list functions in our program.

Exercise

Given the events table, produce a list of names of all people who will pick up their tickets.

Exercise

Given the events table, produce the average number of tickets that were ordered by people with email addresses that end in

".org".

Sometimes, there will be more than one way to perform a computation:

Do Now!

Consider a question such as "how many people with

".org"email addresses bought more than 8 tickets". Propose multiple task plans that would solve this problem, including which table and list functions would accomplish each task.

There are several options here:

Get the

event-datarows with no more than 8 tickets (usingfilter-with), get those rows that have".org"addresses (anotherfilter-with), then ask for how many rows are in the table (using<table>.length()).Get the

event-datarows with no more than 8 tickets and".org"address (usingfilter-withwith a function that checks both conditions at once), then ask for how many rows are in the table (using<table>.length()).Get the

event-datarows with no more than 8 tickets (usingfilter-with), extract the email addresses (usingget-column), limit those to".org"(usingL.filter), then get the length of the resulting list (usingL.length).

There are others, but you get the idea.

Do Now!

Which approach do you like best? Why?

While there is no single correct answer, there are various considerations:

Are any of the intermediate results useful for other computations? While the second option might seem best because it filters the table once rather than twice, perhaps the events company has many computations to perform on larger ticket orders. Similarly, the company may want the list of email addresses on large orders for other purposes (the third option)

Do you want to follow a discipline of doing operations on individuals within the table, extracting lists only when needed to perform aggregating computations that aren’t available on tables?

Does one approach seem less resource-intensive than the other? This is actually a subtle point: you might be tempted to think that filtering over a table uses more resources than filtering over a list of values from one column, but this actually isn’t the case. We’ll return to this discussion later.

A company or project team sometimes sets design standards to help you make those decisions. In the absence of that, and especially as you are learning to program, consider multiple approaches when faced with such problems, then pick one to implement. Maintaining the ability to think flexibly about approaches is a useful skill in any form of design.

Until now we’ve only seen how to use built-in functions over lists. Next [Processing Lists], we will study how to create our own functions that process lists. Once we learn that, these list processing functions will remain powerful but will no longer seem quite so magical, because we’ll be able to build them for ourselves!