4.1 Introduction to Tabular Data

An email inbox is a list of messages. For each message, your inbox stores a bunch of information: its sender, the subject line, the conversation it’s part of, the body, and quite a bit more.

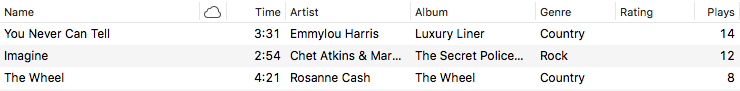

A music playlist. For each song, your music player maintains a bunch of information: its name, the singer, its length, its genre, and so on.

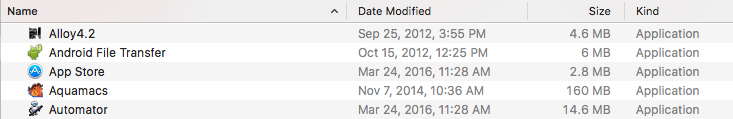

A filesystem folder or directory. For each file, your filesystem records a name, a modification date, size, and other information.

Do Now!

Can you come up with more examples?

Responses to a party invitation.

A gradebook.

A calendar agenda.

They contain information about zero or more items (i.e., individuals or artifacts) that share characteristics. Each item is stored in a row. Each column tracks one of the shared attributes across the rows. For example, each song or email message or file is a row. Each of their characteristics—

the song title, the message subject, the filename— is a column. While some spreadsheets might swap the roles of rows and columns, we stick to this organization as it aligns with the design of data-science software libraries. This is an example of what Hadley Wickham calls tidy data. Each row has the same columns as the other rows, in the same order.

A given column has the same type, but different columns can have different types. For instance, an email message has a sender’s name, which is a string; a subject line, which is a string; a sent date, which is a date; whether it’s been read, which is a Boolean; and so on.

The rows might be in some particular order. For instance, the emails are ordered by which was most recently sent.

Exercise

Find the characteristics of tabular data in the other examples described above, as well as in the ones you described.

We will now learn how to program with tables and to think about decomposing tasks involving them.You can also look up the full Pyret documentation for table operations. The programs later in this chapter use a function-based notation for processing tables, which you can access via the following:

include shared-gdrive(

"dcic-2021",

"1wyQZj_L0qqV9Ekgr9au6RX2iqt2Ga8Ep")Documentation on the function-based table operators is available on a separate page outside of the Pyret documentation.

4.1.1 Creating Tabular Data

table: name, age

row: "Alicia", 30

row: "Meihui", 40

row: "Jamal", 25

endtable is followed by the names of the columns in

their desired order, followed by a sequence of rows. Each row

must contain as many data as the column declares, and in the same

order.Exercise

Change different parts of the above example—

e.g., remove a necessary value from a row, add an extraneous one, remove a comma, add an extra comma, leave an extra comma at the end of a row— and see what errors you get.

check:

table: name, age

row: "Alicia", 30

row: "Meihui", 40

row: "Jamal", 25

end

is-not

table: age, name

row: 30, "Alicia"

row: 40, "Meihui"

row: 25, "Jamal"

end

endis-not, i.e., the test

passes, meaning that the tables are not equal.The check: annotation here is a way of writing is

assertions about expressions outside of the context of a function (and

its where block). We’ll learn more about check in

From Examples to Tests.

people = table: name, age

row: "Alicia", 30

row: "Meihui", 40

row: "Jamal", 25

endtable.

Pyret provides other ways to get tabular data, too! In

particular, you can import tabular data from a spreadsheet, so

any mechanism that lets you create such a sheet can also be used. You

might:

create the sheet on your own,

create a sheet collaboratively with friends,

find data on the Web that you can import into a sheet,

create a Google Form that you get others to fill out, and obtain a sheet out of their responses

With tables, we begin to explore data that contain other (smaller) pieces of data. We’ll refer to such data as structured data. Structured data organize their inner data in a structured way (here, rows and columns). As with images, when we wrote code that reflected the structure of the final image, we will see that code that works with tables also follows the structure of the data.

4.1.2 Extracting Rows and Cell Values

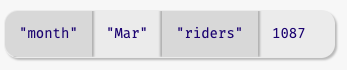

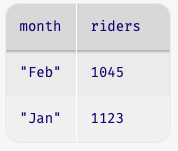

Given a table, we sometimes want to look up the value of a particular cell. We’ll work with the following table showing the number of riders on a shuttle service over several months:

shuttle = table: month, riders

row: "Jan", 1123

row: "Feb", 1045

row: "Mar", 1087

row: "Apr", 999

endDo Now!

If you put this table in the definitions pane and press Run, what will be in the Pyret directory once the interactions prompt appears? Would the column names be listed in the directory?

As a reminder, the directory contains only those names that we assign

values to using the form name = . The directory here would

contain shuttle, which would be bound to the table (yes, the

entire table would be in the directory!). The column names would not

have their own entries in the directory. If we did try to put a column

name in the directory, which value would it map to? There is a

different value in the column for every row. Names in the directory

map to only one value.

Let’s explore how to extract the value of a given cell (row and

column) in the table. Concretely, assume we want

to extract the number of riders in March

(1087) so we can use it in another computation. How do we do

that?

Pyret (and most other programming languages designed for data analysis) organizes tables as collections of rows with shared columns. Given that organization, we get to a specific cell by first isolating the row we are interested in, then retrieving the contents of the cell.

shuttle.row-n(2)shuttle table, extracting row

number 2" (which is really the third row since Pyret counts

positions from 0).If we run this expression at the prompt, we get

This is a new type of data called a Row. When Pyret displays a

Row value, it shows you the column names and the corresponding

values within the row.

To extract the value of a specific column within a row, we write the

row followed by the name of the column (as a string) in square

brackets. Here are two equivalent ways of getting the value of the

riders column from the row for March:

shuttle.row-n(2)["riders"]march-row = shuttle.row-n(2)

march-row["riders"]Do Now!

What names would be in the Pyret directory when using each of these approaches?

Once we have the cell value (here a Number), we can use it in

any other computation, such as

shuttle.row-n(2)["riders"] >= 10001000 riders in March).Do Now!

What do you expect would happen if you forgot the quotation marks and instead wrote:

shuttle.row-n(2)[riders]What would Pyret do and why?

4.1.3 Functions over Rows

Now that we have the ability to isolate Rows from tables, we can write

functions that ask questions about individual rows. We just saw an

example of doing a computation over row data, when we checked whether

the row for March had more than 1000 riders. What if we wanted to do

this comparison for an arbitrary row of this table? Let’s write a

function! We’ll call it cleared-1K.

Let’s start with a function header and some examples:

fun cleared-1K(r :: Row) -> Boolean:

doc: "determine whether given row has at least 1000 riders"

...

where:

cleared-1K(shuttle.row-n(2)) is true

cleared-1K(shuttle.row-n(3)) is false

endRow functions look like, as

well as how we use Row as an input type.To fill in the body of the function, we extract the content of the

"riders" cell and compare it to 1000:

fun cleared-1K(r :: Row) -> Boolean:

doc: "determine whether given row has at least 1000 riders"

r["riders"] >= 1000

where:

cleared-1K(shuttle.row-n(2)) is true

cleared-1K(shuttle.row-n(3)) is false

endDo Now!

Looking at the examples, both of them share the

shuttle.row-nportion. Would it have been better to instead makecleared-1Ka function that takes just the row position as input, such as:fun cleared-1K(row-pos :: Number) -> Boolean: ... where: cleared-1K(2) is true cleared-1K(3) is false endWhat are the benefits and limitations to doing this?

In general, the version that takes the Row input is more

flexible because it can work with a row from any table that has

a column named "riders". We might have another table with more

columns of information or different data tables for different

years. If we modify cleared-1K to only take the row position as

input, that function will have to fix which table it works with. In

contrast, our original version leaves the specific table

(shuttle) outside the function, which leads to flexibility.

Exercise

Write a function

is-winterthat takes aRowwith a"month"column as input and produces aBooleanindicating whether the month in that row is one of"Jan","Feb", or"Mar".

Exercise

Write a function

low-winterthat takes inRowwith both"month"and"riders"columns and produces aBooleanindicating whether the row is a winter row with fewer than 1050 riders.

Exercise

Practice with the program directory! Take a

Rowfunction and one of itswhereexamples, and show how the program directory evolves as you evaluate the example.

4.1.4 Processing Rows

So far, we have looked at extracting individual rows by their position in the table and computing over them. Extracting rows by position isn’t always convenient: we might have hundreds or thousands of rows, and we might not know where the data we want even is in the table. We would much rather be able to write a small program that identifies the row (or rows!) that meets a specific criterion.

Pyret offers three different notations for processing tables: one uses functions, one uses methods, and one uses a SQL-like notation. This chapter uses the function-based notation. The SQL-like notation and the methods-based notation are shown in the Pyret Documentation. To use the function-based notation, you’ll need to include the file specified in the main narrative.

The rest of this section assumes that you have loaded the functions notation for working with tables, using the following line in your Pyret file:

include shared-gdrive(

"dcic-2021",

"1wyQZj_L0qqV9Ekgr9au6RX2iqt2Ga8Ep")4.1.4.1 Finding Rows

Imagine that we wanted to write a program to locate a row that has

fewer than 1000 riders from our shuttle table. With what

we’ve studied so far, how might we try to write this? We could imagine

using a conditional, like follows:

if shuttle.row-n(0)["riders"] < 1000:

shuttle.row-n(0)

else if shuttle.row-n(1)["riders"] < 1000:

shuttle.row-n(1)

else if shuttle.row-n(2)["riders"] < 1000:

shuttle.row-n(2)

else if shuttle.row-n(3)["riders"] < 1000:

shuttle.row-n(3)

else: ... # not clear what to do here

endDo Now!

What benefits and limitations do you see to this approach?

There are a couple of reasons why we might not care for this solution. First, if we have thousands of rows, this will be terribly painful to write. Second, there’s a lot of repetition here (only the row positions are changing). Third, it isn’t clear what to do if there aren’t any matching rows. In addition, what happens if there are multiple rows that meet our criterion? In some cases, we might want to be able to identify all of the rows that meet a condition and use them for a subsequent computation (like seeing whether some months have more low-ridership days than others).

This conditional is, however, the spirit of what we want to do: go through the rows of the table one at a time, identifying those that match some criterion. We just don’t want to be responsible for manually checking each row. Fortunately for us, Pyret knows how to do that. Pyret knows which rows are in a given table. Pyret can pull out those rows one position at a time and check a criterion about each one.

We just need to tell Pyret what criterion we want to use.

As before, we can express our criterion as a function that takes a

Row and produces a Boolean (a Boolean because our

criterion was used as the question part of an if expression in

our code sketch). In this case, we want:

fun below-1K(r :: Row) -> Boolean:

doc: "determine whether row has fewer than 1000 riders"

r["riders"] < 1000

where:

below-1K(shuttle.row-n(2)) is false

below-1K(shuttle.row-n(3)) is true

endNow, we just need a way to tell Pyret to use this criterion as it searches through the rows. We do this with a function called filter-with which takes two inputs: the table to process and the criterion to check on each row of the table:

filter-with(shuttle, below-1K)Under the hood, filter-with works roughly like the if

statement we outlined above: it takes each row one at a time and calls

the given criterion function on it. But what does it do with the

results?

filter-with

produces a table containing the matching row, not the row by

itself. This behavior is handy if multiple rows match the

criterion. For example, try:

filter-with(shuttle, is-winter)is-winter function from an exercise earlier in this

chapter). Now we get a table with the three rows corresponding to winter

months. If we want to be able to name this table for use in future

computations, we can do so with our usual notation for naming values:

winter = filter-with(shuttle, is-winter)4.1.4.2 Ordering Rows

Let’s ask a new question: which winter month had the fewest number

of riders?. This question requires us to identify a specific row,

namely, the winter row with the smallest value in the "riders"

column.

Do Now!

Can we do this with

filter-with? Why or why not?

Think back to the if expression that motivated

filter-with: each row is evaluated independently of the

others. Our current question, however, requires comparing across

rows. That’s a different operation, so we will need more than

filter-with.

Tools for analyzing data (whether programming languages or

spreadsheets) provide ways for users to sort rows of a table

based on the values in a single column. That would help us here: we

could sort the winter rows from smallest to largest value in the

"riders" column, then extract the "riders" value from

the first row. First, let’s sort the rows:

order-by(winter, "riders", true)The order-by function takes three inputs: the table to sort

(winter), the column to sort on ("riders"), and a

Boolean to indicate whether we want to sort in increasing

order. (Had the third argument been false, the rows would be

sorted in decreasing order of the values in the named column.)

In the sorted table, the row with the fewest riders is in the first position. Our original question asked us to lookup the month with the fewest riders. We did this earlier.

Do Now!

Write the code to extract the name of the winter month with the fewest riders.

Here are two ways to write that computation:

order-by(winter, "riders", true).row-n(0)["month"]sorted = order-by(winter, "riders", true)

least-row = sorted.row-n(0)

least-row["month"]Do Now!

Which of these two ways do you prefer? Why?

Do Now!

How does each of these programs affect the program directory?

Note that this problem asked us to combine several actions that we’ve

already seen on rows: we identify rows from within a table

(filter-with), order the rows (order-by), extract a

specific row (row-n), then extract a cell (with square brackets

and a column name). This is typical of how we will operate on tables,

combining multiple operations to compute a result (much as we did with

programs that manipulate images).

4.1.4.3 Adding New Columns

hourly-wage and

hours-worked, representing the corresponding quantities. We

would now like to extend this table with a new column to reflect each

employee’s total wage. Assume we started with the following table:

employees =

table: name, hourly-wage, hours-worked

row: "Harley", 15, 40

row: "Obi", 20, 45

row: "Anjali", 18, 39

row: "Miyako", 18, 40

endemployees =

table: name, hourly-wage, hours-worked, total-wage

row: "Harley", 15, 40, 15 * 40

row: "Obi", 20, 45, 20 * 45

row: "Anjali", 18, 39, 18 * 39

row: "Miyako", 18, 40, 18 * 40

endtotal-wage column computed to

their numeric equivalents: we used the expressions here to illustrate

what we are trying to do).Previously, when we have had a computation that we performed multiple times, we created a helper function to do the computation.

Do Now!

Propose a helper function for computing total wages given the hourly wage and number of hours worked.

Perhaps you came up with something like:

fun compute-wages(wage :: Number, hours :: Number) -> Number:

wage * hours

endemployees =

table: name, hourly-wage, hours-worked, total-wage

row: "Harley", 15, 40, compute-wages(15, 40)

row: "Obi", 20, 45, compute-wages(20, 45)

row: "Anjali", 18, 39, compute-wages(18, 39)

row: "Miyako", 18, 40, compute-wages(18, 40)

endThis is the right idea, but we can actually have this function do a

bit more work for us. The wage and hours values are in

cells within the same row. So if we could instead get the current row

as an input, we could write:

fun compute-wages(r :: Row) -> Number:

r["hourly-wage"] * r["hours-worked"]

end

employees =

table: name, hourly-wage, hours-worked, total-wage

row: "Harley", 15, 40, compute-wages(<row0>)

row: "Obi", 20, 45, compute-wages(<row1>)

row: "Anjali", 18, 39, compute-wages(<row2>)

row: "Miyako", 18, 40, compute-wages(<row3>)

endBut now, we are writing calls to compute-wages over and over!

Adding computed columns is a sufficiently common operation that Pyret

provides a table function called build-column for this

purpose. We use it by providing the function to use to populate values

in the new column as an input:

fun compute-wages(r :: Row) -> Number:

doc: "compute total wages based on wage and hours worked"

r["hourly-wage"] * r["hours-worked"]

end

build-column(employees, "total-wage", compute-wages)total-wage, whose value in each row

is the product of the two named columns in that row. Pyret will put

the new column at the right end.4.1.4.4 Calculating New Column Values

Sometimes, we just want to calculate new values for an existing

column, rather than create an entirely new column. Giving raises to

employees is one such example. Assume we wanted to give a 10% raise to

all employees making less than 20 an hour. We could write:

fun new-rate(rate :: Number) -> Number:

doc: "Raise rates under 20 by 10%"

if rate < 20:

rate * 1.1

else:

rate

end

where:

new-rate(20) is 20

new-rate(10) is 11

new-rate(0) is 0

end

fun give-raises(t :: Table) -> Table:

doc: "Give a 10% raise to anyone making under 20"

transform-column(t, "hourly-wage", new-rate)

endtransform-column takes a table, the name of an existing

column in the table, and a function to update the value. The updating

function takes the current value in the column as input and produces

the new value for the column as output.Do Now!

Run

give-raiseson theemployeestable. What wage will show for"Miyako"in theemployeestable aftergive-raisescompletes. Why?

Like all other Pyret Table operations, transform-column

produces a new table, leaving the original intact. Editing the

original table could be problematic–what if you made a mistake? How

would you recover the original table in that case? In general,

producing new tables with any modifications, then creating a new name

for the updated table once you have the one you want, is a less

error-prone way of working with datasets.

4.1.5 Examples for Table-Producing Functions

How do we write examples for functions that produce tables? Conceptually, the answer is simply "make sure you got the output table that you expected". Logistically, writing examples for table functions seems more painful because writing out an expected output tables is more work than simply writing the output of a function that produces numbers or strings. What can we do to manage that complexity?

Do Now!

How might you write the

whereblock forgive-raises?

Here are some ideas for writing the examples practically:

Simplify the input table. Rather than work with a large table with all of the columns you have, create a small table that has sufficient variety only in the columns that the function uses. For our example, we might use:

wages-test = table: hourly-wage row: 15 row: 20 row: 18 row: 18 endDo Now!

Would any table with a column of numbers work here? Or are there some constraints on the rows or columns of the table?

The only constraint is that your input table has to have the column names used in your function.

Remember that you can write computations in the code to construct tables. This saves you from doing calculations by hand.

where: give-raises(wages-test) is table: hourly-wage row: 15 * 1.1 row: 20 row: 18 * 1.1 row: 18 * 1.1 endThis example shows that you can write an output table directly in thewhere:block – the table doesn’t need to be named outside the function.Create a new table by taking rows from an existing table. If you were instead writing examples for a function that involves filtering out rows of a table, it helps to know how to create a new table using rows of an existing one. For example, if we were writing a function to find all rows in which employees were working exactly 40 hours, we’d like to make sure that the resulting table had the first and fourth rows of the

employeestable. Rather than write a newtableexpression to create that table, we could write it as follows:emps-at-40 = add-row( add-row(employees.empty(), employees.row-n(0)), employees.row-n(3))Here,employees.empty()creates a new, empty table with the same column headers asemployees. We’ve already seen howrow-nextracts a row from a table. Theadd-rowfunction places the given row at the end of the given table.

Another tip to keep in mind: when the only thing your function does is call

a built-in function like transform-column it usually suffices

to write examples for the function you wrote to compute the new column

value. It is only when your code is combining table operations, or

doing more complex processing than a single call to a built-in table

operation that you really need to present your own examples to a

reader of your code.